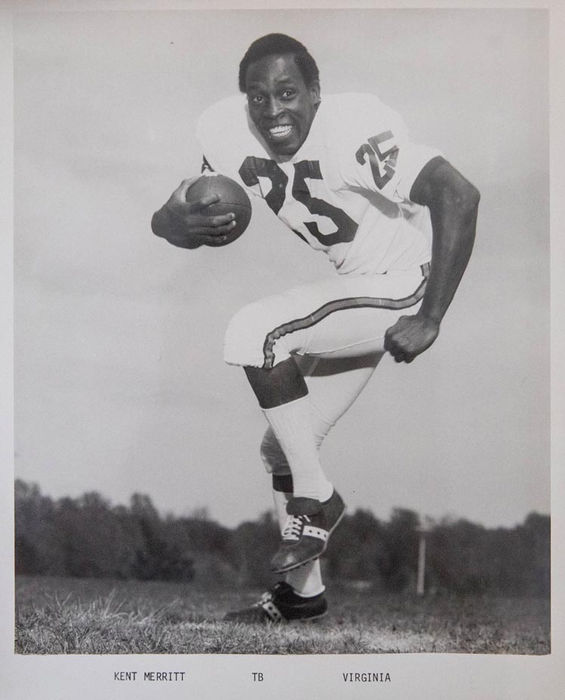

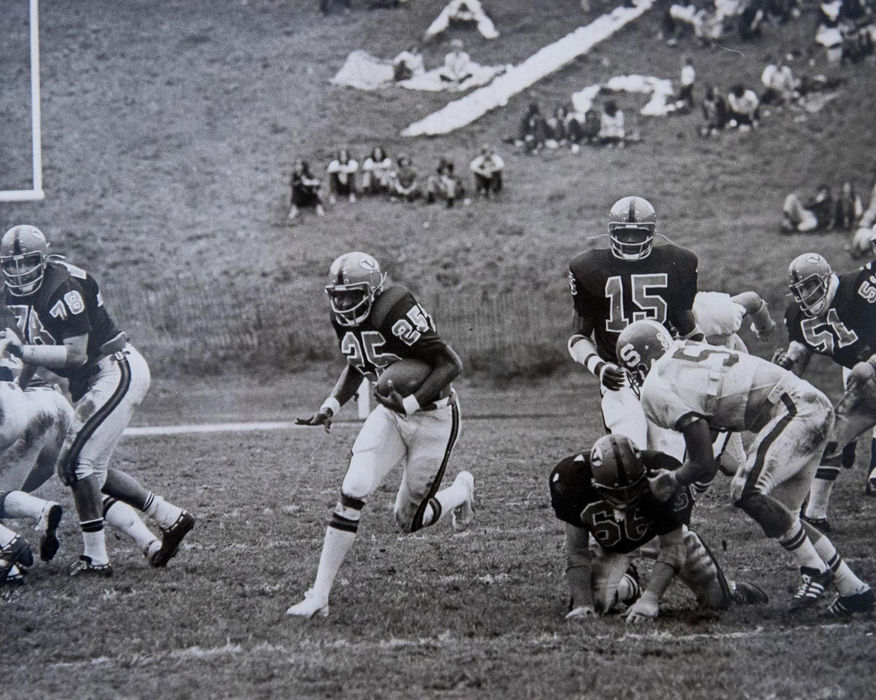

The University’s football team was the last in the ACC to integrate. Partly due to tremendous pressure from progressive students, the school altered its course in 1969 with the signing of Stanley Land, a standout football player from Rockbridge High. A year later, Kent Merritt, John Rainey, and Harrison Davis added their names to the University’s short list of black scholarship athletes.

The story of the four men who broke the color barrier at U.Va. remained mostly untold until 2017, when filmmaker Kevin Edds discovered it while producing his movie "Wahoowa," a documentary that chronicles the history of Virginia Football.

They arrived in Charlottesville not as defiant trailblazers, but young men who simply wanted to play football and stay near home. They enrolled in 1970, but because freshmen had to wait a year, didn't play their first varsity game until 1971—40 years ago.

"We felt we could make a difference as far as winning on the football team," Charlottesville native Kent Merritt said. "I realize now that whole event, that whole time period, meant more to others than we probably realized."

That's not to say there weren't issues. Hate mail and threats arrived for the players from boosters and graduates who weren't happy with the direction the school was moving. It was a time of transition for U.Va., which had also just begun accepting female students.

"It would be inaccurate to try to paint it as the perfect, idyllic scene at U.Va., because it wasn't," Edds said. "I'm sure it was challenging for them."

No one felt that heat more than Davis, who was named the Cavaliers' starting quarterback.

Now over 40 years later, the memories aren't all about football. One relationship the players have maintained is with their freshman coach, who helped guide them in their transition to college. That man was Al Groh, who later became the head coach.

“I never expected to have that kind of support from him… Groh was all about winning and having the right attitude towards the game. He didn’t play any of that shit,” said Davis.

Per Land: "It's not uncommon to get a text message from Coach Groh on holidays, and a telephone call if he's passing through the area.”

Rainey echoed the same: “Coaches played a big role in protecting us when we were there.”

“I was certainly alert to the fact that these four kids had an enormously different adjustment to make than the other kids on the team,” said Groh. “They handled everything beautifully. We’re very proud of the four of them.”

Through the unflinching help of their support network, Davis and his teammates were able to triumph over the adversity they faced. The bonds created on the football field would later allow Davis and Merritt to seek companionship and solidarity with like-minded individuals within an organization of their own. The underpinnings of what would later be called the Eta Sigma Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi began at U-Heights apartment complex in the summer of 1973. Other African Americans also living nearby in the complex were Brothers of Kappa Alpha Psi. Davis recalls being inspired by these “educated men” because they offered them knowledge and insight on what it meant to be a successful black man, “they were teachers in the area and they were educated and about something; academically we were all challenged by their diligence and fortitude and sought to be a part of what they represented.”

Merritt, Land, Rainey, Harrison Davis were all-state performers who had multiple options for college. All four chose to go to UVA and make history in the process.

“We came to play sports and athletics,” said Merritt. “We didn't really come to do anything earth-shattering. We thought we could at least improve the program while we were here.”

"We just wanted to go somewhere and play football and win football games,” Land added. “We weren't so much aware of what we were doing until after we graduated, really.”

You can still find some of their accomplishments in the UVA record books. But the ones of which they are most proud are earning their degrees and making those around them re-think what they thought they knew about African Americans as players and as students.

“After you get away from it and look back and reflect, you start to understand what that really meant,” said Land. “That was a big event in the history of UVA.”

Rainey recounted a conversation he had with a teammate that told him just what their decision had meant.

“In my third year, he said 'John, I didn't know what to expect when they said Blacks were coming to UVA. I had to call my parents liars because of the lies they told me when I was coming up about Black people. You all proved to me that all of the stuff my parents told us was a bunch of crap. And I want to apologize for that'. If we did nothing else, maybe we showed a few people who blacks really are.”

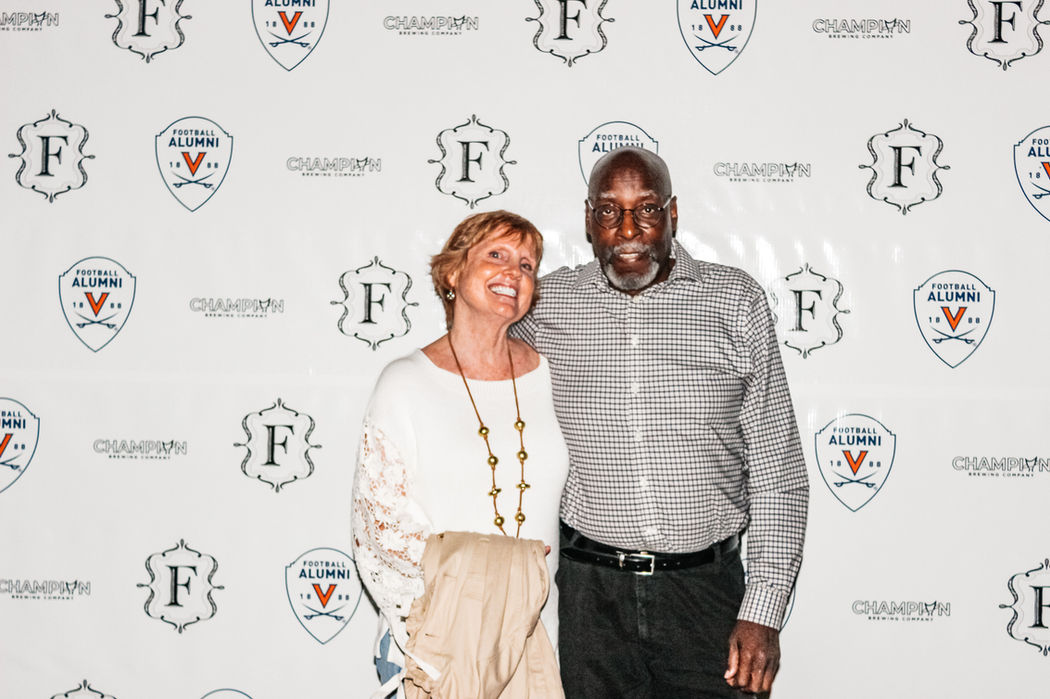

Land lives in Houston, Merritt is in Charlottesville, Harrison is in Florida, and Rainey lives in the Tidewater area. The four try to attend a game together annually.

"We didn't see ourselves as pioneers, we were just part of the football team," Land said. "As I look back now, some 40 years, it was a tremendous change in our lives at that time, and certainly a tremendous change for the university. We were Groundbreakers."

https://news.virginia.edu/video/groundbreaking-integration-virginia-football